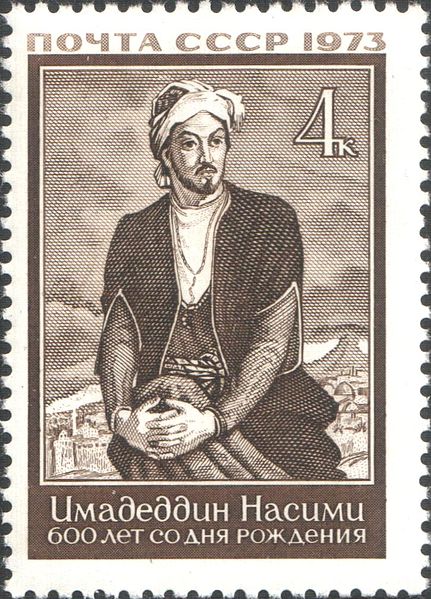

The Ḥorūfī movement, initiated by Faḍl Allāh Astarābādī (1339-1394) and based on his metaphysical doctrine, to the present day exerts a lasting influence on various religious and literary currents beyond Iran. This applies first of all to the development of turcophonic literature, in which the dīwān poetry of ḥorūfī-oriented authors is firmly anchored. In ʿImād ad-Dīn Nasīmī, a direct disciple of Faḍl Allāh, Azerbaijan found one of its most prominent national poets. The legacy of the Ḥorūfī movement also continues to influence the religious self-image of the Alevi and Bektashite milieu, which under Ottoman rule stood in a complex oppositional relationship to Sunni orthodoxy. However, despite the broad reverberation of Faḍl Allāh’s doctrine, there is still no critical edition of the works attributed to him.

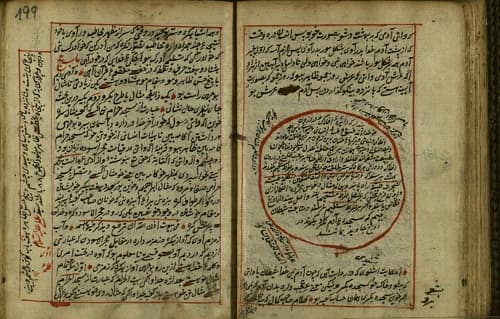

In Words of Power Orkhan Mir-Kasimov, who works at the London Institute of Ismaili Studies and has already written numerous articles on the Ḥorūfī movement, presents the first comprehensive analysis of the content of Faḍl Allāh’s main work, the ǧāvedān-nāme (the book of eternity). To arrive at a description of Faḍl Allāh’s original doctrine, he compared four available manuscripts. As an introduction, the author discusses the biography and followers of Faḍl Allāh, the current state of research on the Ḥorūfī movement, as well as the structure and language of the ǧāvedān-nāme. The central aspects of the doctrine are then analysed in three main parts.

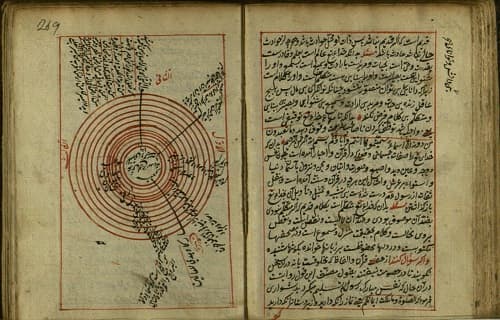

Mir-Kasimov’s outline alone already represents a first elaborate preparation of the content of the ǧāvedān-nāme, for the manuscripts examined have a seemingly enigmatic peculiarity in common: Their paragraphs are semantically disconnected from each other, strung together incoherently, as if they had been cut out, jumbled up and put together again in random order. For his analysis the author was able to group the paragraphs thematically, thus restoring the context and producing a readable text. In his introduction, he discusses the plausibility to whether the remarkable surviving form of this work could be due to a strategy of obfuscation following the Shiite principle of Taqīya, for example, to escape persecution by orthodox ʿUlamāʾ. However, since the ǧāvedān-nāme does not contain any openly heretical statements and is oriented towards the legitimistic argumentation of classical Quran commentaries, he considers it more likely that the formal inaccessibility of the work is rather an expression of the doctrine itself, according to which all principles must be dissolved before the true understanding of divine truth can be gained.

Cosmogony and cosmology: The language of creation

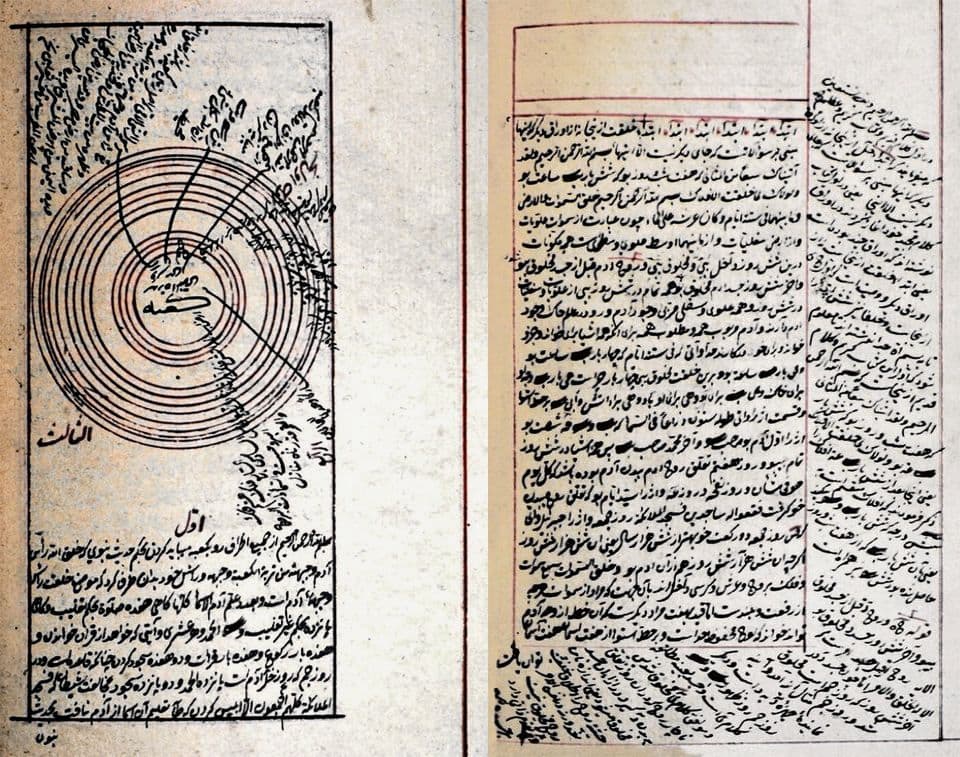

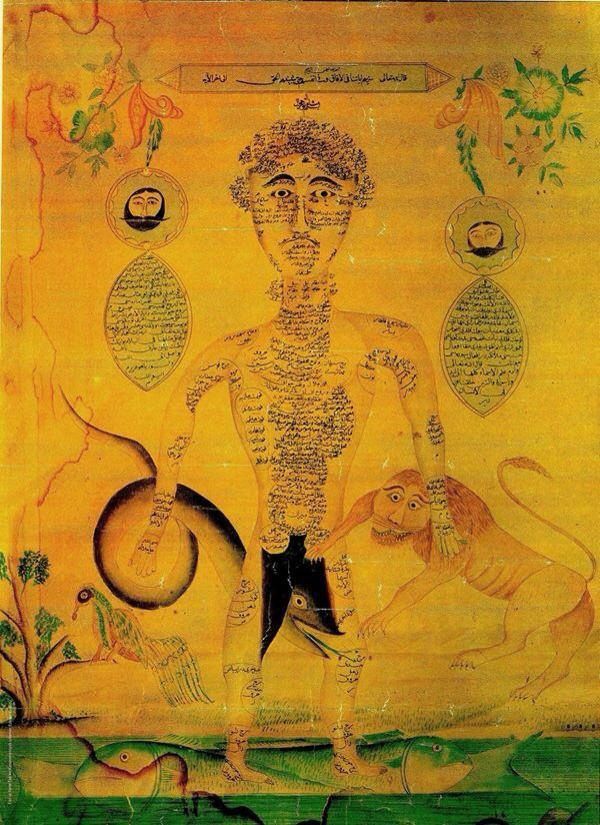

In part one Mir-Kasimov develops a foundation for understanding the doctrine. Faḍl Allāh describes the structure and evolution of all entities of the universe as the evolution of a language that descended from a prehistoric, absolute and divine unity into all spheres and atoms of the universe. According to this metaphysical concept, the universe is pronounced and written down in the sense of a divine language, which is why Mir-Kasimov describes the doctrine’s method of functioning as semantics, morphology and syntax. In the beginning, there is the divine unity as a purely ontological, creative force in which no duality or differentiation exists and each meaning is identical with its respective linguistic expression: Name and the named are one, subject and object coincide. The unity is not recognizable by thought or imagination and can at best be described in a negating sense (e.g. it can only be stated what it is not). The original Word of God here consists of indivisible elements, the so-called words (kalemāt), which in a sense can be understood as phonemes of creation. From them, names are formed which represent the instrument of creation: They transport metaphysical meanings (maʿnā) and truths (ḥaqīqa) into all being and thus constitute the principle of being of every living entity and object, whether it really exists or is merely potential.

Prophetology: The descent of the word and its return to its origin

The second part describes the conveyance of the divine Word between God and creation by the means of man in his archetypal function as a prophet (p. 237). The ǧāvedān-nāme considers man as the ideal manifestation of the divine Word and assigns to him and his physical form a passive role necessary for the unfolding of creation (p. 217f). Here Mir-Kasimov describes in detail how the doctrine deals with the theological question whether the divine revelation can be expressed in human language and spells out its central concepts: The descent of revelation (tanzīl) into the outer forms (ẓāher) and the ascent and return to its origin (taʾwīl), which leads to the revelation of the inner meanings of all things (bāṭen). Faḍl Allāh uses the stories of the prophets as examples and as a basis of legitimation, but in contrast to classical commentaries on the Quran, no earlier commentators are mentioned and the derivation in the ǧāvedān-nāme is based exclusively on his individual mystical experience. Certain doctrinal positions are assigned to the individual prophets. Another striking feature of the ǧāvedān-nāme is its proximity to the Ismaili concept of Islamic prophetology: Faḍl Allāh extends the principle of interpreting the Quran and Sunna equally to Jewish and Christian sources.

Follow the blog

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Receive updates about the Toolbox and other fresh content, you may cancel anytime.

Soteriology and Eschatology

The possibility of knowledge and redemption of mankind, which is dealt with in the third part, allows Mir-Kasimov to describe ambivalences and obvious inconsistencies of the doctrine and to place them in the context of the work’s time. For example, Faḍl Allāh defines the identity of the Messiah contradictorily: On the one hand, the ǧāvedān-nāme fulfils the expectation of Sunni doctrine by calling Jesus the Saviour, on the other hand, it describes the Mahdi according to Shiite doctrine as a descendant of Fatima. Here the partly indissoluble argumentation structure of the ǧāvedān-nāme becomes more understandable through the explanations and references that Mir-Kasimovs provides in his footnotes.

In his conclusions, Mir-Kasimov addresses three main questions: The possible reading of the work as a commentary on the Quran, the still to be specified position of the doctrine between Sufism and esoteric Shia, and the influence of Christian apocalyptic texts on the messianic tendency of the Ḥorūfī movement.

Conclusion

Words of Power offers interesting insights and starting points for a whole range of research fields. The ǧāvedān-nāme reveals an original approach to Islamic, Jewish and Christian sources, including Apocrypha. It contains references to occult sciences such as alchemy, astrology, and the mysticism of numbers and letters, and in places shows indirect parallels to the theological concepts of the Ismailites, the metaphysics of Ibn ʿArabī and the teachings of Naǧm ad-Dīn al-Kūbrā. Its inner ambivalence concerning theological questions, such as the interpretation of the anthropomorphic attributes of God in the Quran, makes it interesting for research in the history of theology. As Mir-Kasimov mentions, it could also shed light on the relationship between Sufi networks and Shiite orthodoxy during and immediately after the Mongol rule. For the study of the Alevi and Bektashite traditions of Turkey and the Balkans, where the heritage of the Ḥorūfī movement is still alive and of importance, this book could also be a strong stimulus, especially since the relationship of later Ḥorūfī poets to Faḍl Allāh’s original doctrine has not yet been sufficiently investigated.

Mir-Kasimov’s writing style is appropriate for the complexity of the subject. Although his use of language may seem redundant in places, this is due to the source, as Faḍl Allāh gradually differentiates his basic definitions more and more until their individual aspects are intricately intertwined. In his analysis, the author quotes from the Persian original in appropriately extensive English translations. He avoids overloading the already complex matter by discussing the thematic and ideological influences of the ǧāvedān-nāme mainly in summary form in his conclusions and footnotes, where a wealth of references for further research can be found.

The intellectual depth of the ǧāvedān-nāme makes the extensive appendix particularly helpful. In addition to a general index, a glossary of the most important terms makes it easy to get started and allows looking up certain terms employed by Faḍl Allāh, some of which he uses in a very specific way. An inventory of the hadiths and traditions discussed, an index of Bible and Quran quotations, and a considerable Persian textual apparatus of all quotations from the ǧāvedān-nāme allow for tracing the sources.

Words of Power can be explicitly recommended to a professionally interested readership and will hopefully inspire many new research questions in relevant disciplines.

Words of Power can be ordered directly from the publisher: I.B. Tauris (since 2018 an imprint of Bloomsbury).

Bibliography

Mir-Kasimov, Orkhan (2015): Words of Power. Ḥurūfī teachings between Shiʿism and Sufism in medieval Islam. The original doctrine of Faḍl Allāh Astarābādī. London/New York: I.B. Tauris (The Institute of Ismaili Studies, Shiʿi Heritage Series, Vol. 3).

Further reading

For further reading I compiled this small bibliography on the movement, its actors and sources.

Notes

This review was published in German in the Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes No. 109 (2019) and is therefore not subject to the Creative Commons license I normally use. For this blog article the transliteration of Persian terms and names has been changed to the e/o system.

Recommended form of citation

Vincent Vaessen: Review of: Mir-Kasimov, Orkhan: “Words of Power. Ḥurūfī teachings between Shiʿism and Sufism in medieval Islam. The original doctrine of Faḍl Allāh Astarābādī”. London/New York: I.B. Tauris 2015 (The Institute of Ismaili Studies, Shiʿi Heritage Series 3), in: Wiener Zeitschrift für die Kunde des Morgenlandes 109 (2019), translated from German into English by the author, Publication available online.