While doing research for my bachelor thesis on representations of Iran in modern travelogues, I wanted to get a first impression about the latest trends in online book sales, so I skimmed through Amazon’s best-selling books on Iran. There I came across an odd phenomenon: The Amazon item list was literally littered by dozens upon dozens of random Iran travel notebooks with generic cover designs and titles. At first I didn’t pay much attention to them, but as I scrolled down page after page and kept stumbling upon new, only slightly different versions of the same item, including some ridiculously bizarre ones, I became curious about what mechanism might be behind it and who would benefit from it. What I could not foresee at this point, was that I would soon come across clearly problematic and even xenophobic notebook designs.

After counting well over a hundred notebook variations intended for journeys to Iran, I not only felt curious, but also suspicious and provoked. Their uninspired design variations were tiresome, some of them were absurdly random and a few really irritated me. Take this one below for example, which in hindsight is a rather harmless example compared to my later findings: It locates Iran on a clinched world map, where Iran supposedly consists of Afghanistan, Pakistan, India, South-East-Asia and a part of China, directly neighbouring Australia, with Iran itself not even being part of this grotesque construct.

Presumably a poorly developed algorhythm or failing customization would be to blame for this particular design and some of the others, with automated hypercapitalism as the ultimate excuse for the virtualised commodification of individual travel experiences. The large amount of notebooks appearing in my Amazon search results showed how vendors rely on generating a sheer quantity of generic, pseudo-customized products without any quality control, counting on occasional buyers and the ignorance and carelessness of the public. Could these unappealing notebooks be of any use for my research on representations of Iran and the imagined ‘East’, or were they in the end just another form of internet background noise? After all, with the internet being world’s largest and probably most devious market space, crazy clickbait flooding our screens and untransparent algorhythms guiding our access to news and our use of social media, an automated online sales strategy that allows for capitalizing on travel accessories shouldn’t come as a big surprise.

To see tourism to Iran being turned into a consumable commodity in such an automated way on Amazon had caught my interest. The randomness and genericness of the notebooks’ designs and their seemingly innocuous captions, promising ‘a fun travel adventure’, and the simulation of uniqueness reminded me of the problematic perceptions of authenticity, individuality and ‘the other’ that I had encountered in many of the travel blogs, vlogs and interchangeable bestselling books about trips to Iran. Could these notebooks be one of the accompanying symptoms of the consumerist sell-out of tourism to an imagined ‘exotic’ and ‘mystic’ East? As with most things, judgement is not that easy, and when you read theory, you tend to theorize everything as soon as a pattern emerges. Before we continue, let’s take a look at some of the findings on Iran first and try to categorize them, because these also are the templates for clearly problematic notebooks available for other countries and ’causes’.

The essence of traveling: Unicorns, avocados, and “a very personal adventure”

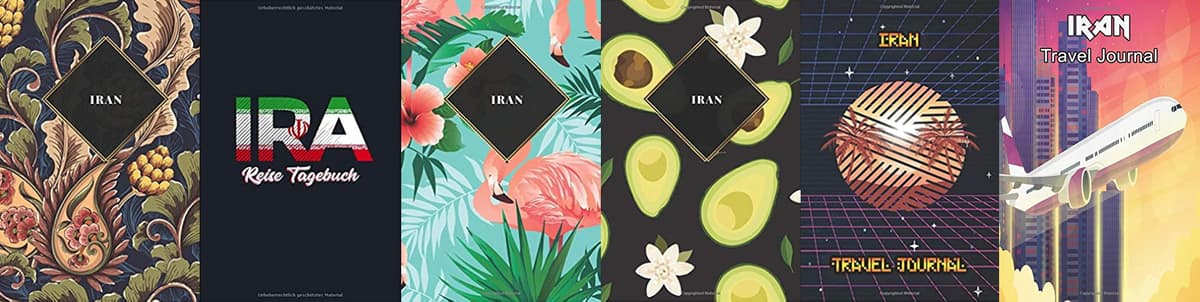

The arbitrariness of the designs can best be noticed in the variety of available background images: flamingos, unicorns, avocados, random wallpaper patterns. Other designs feature common travel symbols like airplanes and country flags. We can distinguish four main types or parent models from which child items are generated:

1. Simple captions on varying backgrounds, like My travel journal, Let the adventure begin, Persia or Iran, etc. As we can see, country codes colored with the national flag like “IRA” or “IRN” are also easily integrated into the designs.

2. Notebooks with quotes & mottos, ranging from Iran is my valentine, Unicorns are from Iran, Iran is calling and I must go, I don’t need therapy, I just need to go to Iran, My Iran bucket list up to Iran Soccer Fan Journal, Iran is boring and even Fuck Iran.

3. Notebooks designed for buyers with an Iranian background: I may live in xyz, but my story began in Iran, Growing in Europe/America with Iran roots, Made in America/Canada/Britain with Iranian Persian parts, Iran: It’s in my DNA, You wouldn’t understand, it’s an Iranian thing, Have no fear, the Iranian is here, etc. These designs are available to many country combinations and other product categories, such as coffee cups, t-shirts and hoodies.

4. Gendered notebooks for women or men, for example Just a girl who loves Iran, Travel journal for men.

From the examples in the third category it becomes clear that the notebooks are not only sold as a tourism accessory, but generally speaking represent a sales strategy that attempts to siphon off all conceivable target groups, amongst which are also potential buyers supposedly having Iranian roots but not living in Iran.

A distinguishing feature that could have set a notebook apart from these generic items would have been for example content adapted to Iran, such as some pages with an overview of the Persian alphabet and common words and phrases for a simple conversation with Iranians. None of the travel notebooks offer such features, they have blank pages and perhaps a general travel checklist. Out of over a hundred available items we can single out only eight items which designs are tailored to Iran: four showing either the map or an actual (yet still random) photograph of Iran and another four captioned with “Persia” and showing the emblem of the Pahlavi dynasty.

Creators of indifference?

It remains unclear to me how all of these designs are exactly made. They could have been generated by a script with only little human supervision, by selecting accordingly tagged background images from an image pool and captioning them with pre-defined titles with the country’s name or a city as a variable. This could be true for those notebook designs that are available for numerous other countries, too, with only the countries’ names being changed. They also could have been designed by hand by the vendors, as demonstrated for example by Rob Cubbon, who not only sells notebooks on Amazon, but also sells online courses on how to be a successful notebook vendor.

Cubbon is by far not the only one: There is a growing scene of blogs and vlogs on the topic in various languages, where vendors, instructors and consultants first give free basic advice on successful notebook selling via Amazon, and then funnel their customers to paid content, thus generating their own flow of income by feeding off the interest in the notebook business itself via courses, affiliate marketing and ad revenue. It has grown into a meta-business which is desperate to generate more branches and niches for creating so-called passive income, an increasingly popular trend which I call the business of “consulting consultants on consulting consultants consulting consultants” (ad infinitum).

How Amazon capitalizes on the notebook business

Selling travel journals is a market niche that apparantly is worth it: I found over 50 active seller accounts in the Amazon travel notebook business, who in the strict sense of the word and according to Amazon jargon are not defined as sellers, but as vendors, which means that their inventory is owned, sold and shipped by Amazon itself. In this model, vendors act as wholesale suppliers selling their items to Amazon, which then acts as their online retailer. This relationship between vendors and Amazon is mutually beneficial: vendors benefit from Amazon’s brand trust and credibility as well as a variety of tools allowing to target desired audiences and markets, while Amazon gains profit from procurement costs, category referral fees, FBA (Fulfillment by Amazon) fees and a general service fee for the selling plan. The items may be in stock at Amazon’s warehouse or, as in our case with travel notebooks, can be printed on demand whenever they are bought.

Whether created by script or by hand, the creation and selling of items can easily be managed by the vendors via Amazon’s platform CreateSpace, which offers them access to manufacturing and print-on-demand options. In fact, designing and selling a notebook can be done entirely through Amazon’s web services.

The uneasy easiness of automated item generation

Automatically generated items are not a new phenomenon on Amazon, they just mostly escape general attention. Instead of tediously designing every single item, some companies have resorted to using a software script that can generate whole families of products in bulk by deriving individual items from parent items according to certain rules. This dragnet-like method allows sellers to offer products for practically all imaginable target audiences worldwide, creating a veritable deluge of items, or as Louise Matsakis in Wired put it: “a consumer product designed to cater to a human desire that may never exist”((Matsakis, Louise (2019): How Auschwitz Christmas Ornaments Ended Up for Sale on Amazon, in: Wired, 12/02/2019, accessed on 29/07/2020.)).

2017 a controversy arose when German company ToasterNet became the subject of ridicule and criticism from the online community for using bots to design mobile phone covers, which resulted in many—to put it mildly—unusual covers being offered, with stock photo depictions of plumbing, medical procedures, a man wearing a diaper, sex toys, water taps, drug abuse, and various sexualised images.((Vincent, James (2017): A bot on Amazon is making the best, worst smartphones cases, in: The Verge, 10/07/2017, accessed on 29/07/2020.)) The company stated that it partly did not know how exactly these bizarre designs were generated and finally gave up on its selling practice, also because the magnitude of items was not managable anymore.((Eisenbrand, Roland; Peterson, Scott (2017): This is the German company behind the nightmarish phone cases on Amazon, in: OMR, 25/07/2017, accessed on 30/07/2020.)) Up until this point, the products on offer had been ridiculous and at best uncomforting, but in early 2019 Amazon and the Wish platform were forced to withdraw a whole range of items from sale after having being publicly called upon by the Ausschwitz Museum in Poland.((Staudenmaier, Rebecca (2019): Amazon under fire over Auschwitz ‘Christmas ornaments’, in: Deutsche Welle, 01/12/2019, accessed on 29/07/2020.)) Two chinese vendors had been offering Christmas decorations with designs showing pictures of the Auschwitz extermination camp, and even bath towels incorporating the inhumane, depreciating slogan written on the camp’s gate (“Arbeit macht frei”) had gone up for sale.

While some sellers on Amazon can certainly be accused of trying to circumvent the sales guidelines in order to market harmful, misanthropic and racist content, our case of travel notebook designs at first glance seem to spring from a harmless, blindly automated process in hunt for cheap profit.

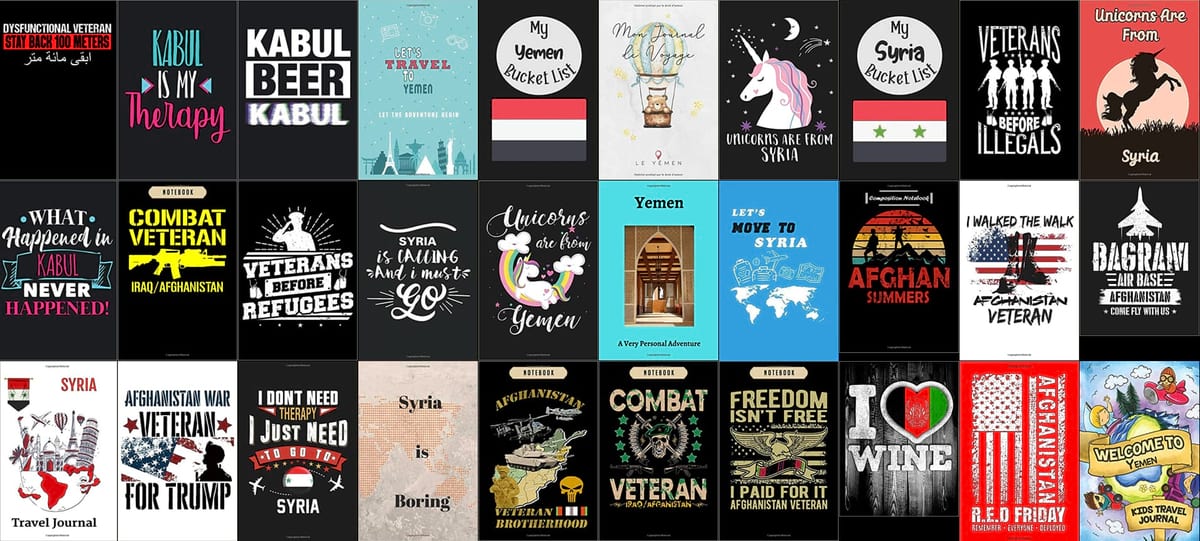

“What happened in Kabul never happened!”

So how could the offered notebooks be problematic? Again, a simple search on Amazon drew me deeper into the matter. Curious what notebooks Amazon might have in stock for Afghanistan, in October 2020 I found a staggering 37-page list of items on Amazon and was taken aback by some of the finds. Promoting happy travel accessories suddenly gains an undertone of ignorance, gloat and malice. Between the obligatory “Kabul is my therapy” or “Unicorns are from Afghanistan”, you will find notebooks promoting alcohol and getting drunk in Afghanistan, which is problematic on several levels.

The notebooks shown above override the agency of Afghans and burrow their collective and individual preferences by associating their country with excessive drinking. The designs promoting heavy drinking are not only insensitive to the religious and moral preferences, but also to the laws under which Afghan citizens live: In Afghanistan, the import, production, sale and consumption of alcohol is punishable under criminal law. However, diplomatic missions and international organisations may import alcohol for their foreign personnel and tourists are allowed to import up to two litres on entry. Thus the problem with the alcohol promoting notebooks lies in a certain perspective, and either notebooks were blindly generated with disregard for the country itself, or they are possibly intended for random buyers, as mere variants of other alcohol themed notebooks for other countries. The undertone gets even more malign when we look into the actual recent history of excessive consumption of alcohol by foreign troops in Afghanistan, and ask ourselves: who actually has been getting drunk in Kabul?

Alcohol abuse by foreign military forces in Afghanistan

After an airstrike ordered by German forces and carried out by US air support killed 125 Afghan civilians near Kunduz City on 3 September 2009, then head of ISAF General Stanley McChrystal had tried to contact personel on the ground, who were inable to react accordingly due to drunkenness.((The Telegraph (2009): Alcohol banned on Afghanistan base after troops party too hard, in: The Telegraph, 08/09/2009, accessed on 17/08/2020.)) Following this deadly pre-emptive strike, Germany so to speak pre-emptively offered the victims’ families 5000 dollars each as compensation for their loss, but the money often never reached them, because the German government handed it out to local leaders and warlords instead of to the families directly((Graupner, Hardy (2011): Afghan families seek compensation for civilian deaths in Kunduz, in: Deutsche Welle, 01/09/2011, accessed on 17/08/2020.)). Despite the outcry of the Afghan community and the victim’s families, in 2013 German Colonel Klein who had ordered the strike was promoted and given a new leading function((Hasrat-Nazimi, Waslat (2012): Afghans condemn German colonel’s promotion, in: Deutsche Welle, 13/08/2012, accessed on 17/08/2020.)), and finally, “Germany’s top criminal and civil court, the Bundesgerichtshof […] ruled that the state need not compensate relatives of the victims”((Deutsche Welle (2016): German state not liable to pay compensation to victims of 2009 Kunduz airstrike, in: Deutsche Welle, 06/10/2016, accessed on 17/08/2020.)).

Because of cases of abuse on duty, the consumption of alcohol was banned for US troops in Afghanistan, which led to the closing of at least seven bars operated by ISAF serving tax-free beer and wine, one of them even called Tora Bora, “where Coronas cost a couple of Euros and Marvin Gaye blasts from the speakers hung above the hockey jerseys on the wall”((Madden, Steve (2010): Building Bridges: While on a mission to bring 50 new bikes to Kabul, Steve Madden remembers an old friend, in: Bicycling, 08/06/2010, accessed on 17/08/2020.)). Naming a bar “Tora Bora” speaks volumes. During the early years of the Afghanistan mission, the U.S. military presented Tora Bora as a mysterious, impenetrable cave system through which one had to bomb one’s way by force, legitimizing the indiscriminate elimination of anybody in the area, basically establishing a kill-zone, a drop-off territory for all bombs available. It also goes hand in hand with a certain view on Afghan “tribespeople”, who since over 100 years are being described as savage, fanatical, violent and eager for war, therefore deserving a hard-handed approach.

Alcohol abuse can also be found as a downplaying argument when investigating its role in atrocities committed by US troops, as in the case of 38-year old Army Staff Sgt. Robert Bales, who on 11 March 2012 left camp Belambai at 3 a.m. and murdered 16 Afghan villagers, nine of which were children, and set 10 of his victims’ bodies on fire. During the trial, his civilian attorney rejected the influence of alcohol being essential to the crime((BBC News (2012): Afghan massacre US soldier ‘reluctant to serve’, in: BBC News, 16/03/2012, accessed on 17/08/2020.)), but before Sgt. Bales had been charged, an anonymous official in a simplistic explanatory statement already had told the New York Times that Bales had been drinking with two comrades that night: “When it all comes out, it will be a combination of stress, alcohol and domestic issues—he just snapped”((Schmitt, Eric; Yardly, William (2012): Accused G.I. ‘Snapped’ Under Strain, Official Says, in: New York Times, 15/03/2012, accessed on 17/08/2020.)).

The scorn and desecration of innocent victims even continues beyond their murder: Ben Roberts-Smith, who killed a disabled young man (with allegedly 10-15 bullets), was later photographed drinking beer from the man’s prosthetic leg as a ‘souvenir’, a war trophy. As many more nefarious boozy images of other military personel emerged, it became clear that this prosthetic was frequently used as a beer vessel in drinking gatherings of U.S. troops. These absolutely dispicable acts were labeled as a way for soldiers to “decompress” in recent court hearings((McKinnell, Jamie (2021): Ben Roberts-Smith defamation trial told soldiers drank beer from dead Afghan man’s prosthetic leg, in: ABC News, 07/06/2021, accessed on 07/06/2021)).

Considering the decades of suffering of the Afghan people, some of the monstrocities committed under influence, the party slogan “What happened in Kabul never happened” shown on a notebook design above has a particularly mocking effect. Especially given the fact that for example the US army, Australian forces as well as mercenaries (euphemistically referred to as contractors) have repeatedly committed atrocities and have been reluctant to admit to their war crimes. In the context of Afghanistan, a fun slogan seemingly fit for a weekend party trip to Berlin, London or Amsterdam becomes a slogan describing the politics of conceilment and denial of crimes against humanity. This is an unfortunate circumstance brought about by the arbitrarily designed products on Amazon, and it doesn’t seem to bother the vendors themselves or Amazon.

The repertoire of problematic, insensitive designs is by no means unique to Afghanistan, but affects a whole range of countries, including Syria and Yemen in particular, as the following examples make clear:

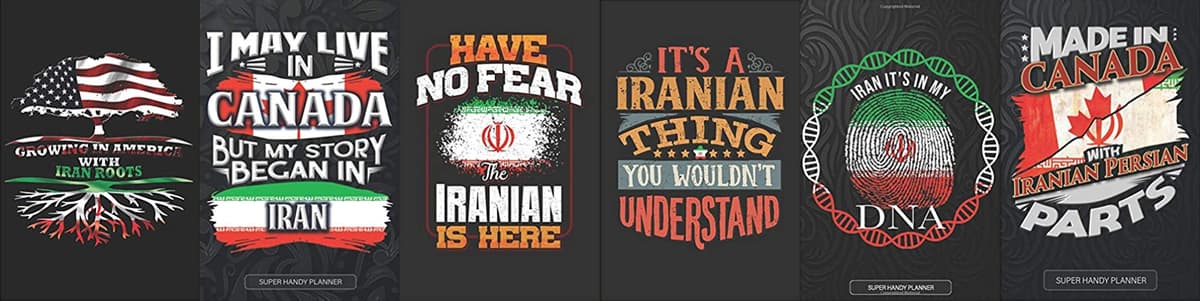

Notebooks for veterans

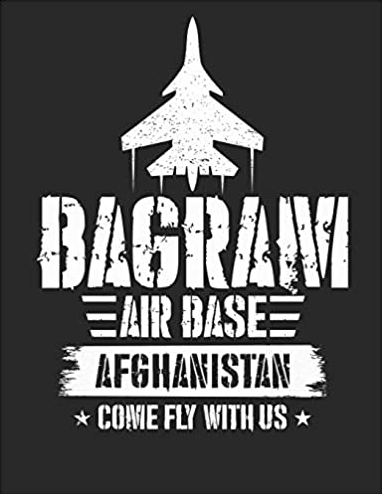

As can be seen from the above examples, there is another, even more problematic niche of Amazon products: Notebooks for veterans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq. For example, “Bagram Air Base – Afghanistan, come fly with us” is an outright cynical and perfidious caption for a notebook. It not only trivializes the US’ inhumane Afghanistan policy and normalizes its aggressive intervention policy, which conveniently brushes away civilian deaths as so-called ‘collateral damage’, but also commodifies and markets a dark place of lawlessness and torture. Close to the Bagram Airforce Base in Afghanistan, where US personel enjoyed relaxing in coffeeshops, watching movies at a cinema and feasting at fast food restaurants, the US maintained an internment camp now called Parwan Detention Facility, and while US forces in later years were concerned with enhancing Wifi access on site in order to improve FaceTime quality of their personnel((Garland, Chad (2018): Bagram Wi-Fi overhaul will give airmen better ‘FaceTime’ with family, in: Stars & Stripes, 03/01/2018, accessed on 07/08/2020.)), the site’s prison previously held up to 600 detainees without a protection status as prisoners of war, without charge, without access to lawyers and without trial. There have been reports of mistreatment and torture by US military personnel((Graham-Harrison, Emma (2014): US finally closes detention facility at Bagram airbase in Afghanistan, in: The Guardian, 11/12/2014, accessed on 24/01/2021.)), and prisoners have died as a result((Bazelon, Emily (2005): From Bagram to Abu Ghraib, in: Mother Jones, March/April 2005, accessed on 05/03/2021.)). 2014 the base was transferred to Afghan forces, under whose control however torture did not stop.((Fenton, Jenifer (2019): What happened to prisoners at Bagram, ‘Afghanistan’s Guantanamo’?, in: Aljazeera, 11/02/2019, accessed on 07/02/2021.))

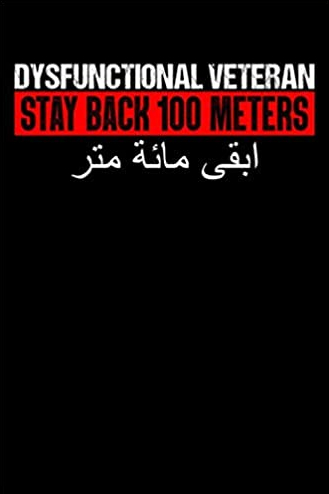

A notebook captioned “Dysfunctional veteran – stay back 100 meters” cynically plays into veterans suffering from PTSD, deliberately addressing an Arabic-speaking public as a shooting target, with PTSD functioning as a mere excuse and vindication. Veteran merchandize survives in a popular culture that celebrates and heroifies veterans as fighters in ‘just’ wars, yet PTSD and its terrible consequences could be a powerful reason to thoroughly rethink the US’ destructive foreign policy.

Another veteran notebook captioned “Afghanistan Veteran Brotherhood” shows a map of Afghanistan being overrun by a tank, with army helicopters and fighter jets flying over. Certainly, these notebooks and the messages conveyed in their designs do not reflect the view of all veterans, however, it is precisely these products that can be instrumentalized for political purposes by using the celebratory nationalist discourse as a vehicle. Digging deeper into Amazon’s search results, we find notebooks that seek to denounce the neglect of veterans by marking refugees as the people to blame:

The question is whether these are merely online products or if we can actually encounter these xenophobic slogans in real life. If one searches for the slogans “Veterans before refugees” and “Refugees before illegals,” one usually comes across internet stores selling patriotic, Republican, pro-firearm, alt-right and Trump merchandizing. Moni Basu describes in an article how she encountered the slogan “Veterans before refugees” on T-shirts of participants of an NRA convention((Basu, Moni (2017): From Gandhi to guns: An Indian woman explores the NRA convention, in: CNN, 05/10/2017, accessed on 15/01/2021.)). Their argument that refugees are helped with housing and being taken care of while veterans in need are not, comfortably ignores the fact that homelessness amongst veterans is a persisting issue that has been left unsolved for decades.

During the Trump campaign and his presidency we saw online right-wing activism misusing the veterans’ cause for their xenophobic and racist attitude against immigrants and refugees gain significant traction((Nahan, Ian (2017): Pitting homeless vets against Syrian refugees: A theme for online right-wing activism, in: Sociological Images, 24/05/2017, accessed on 02/03/2021.)), with memes and fake news about refugees being shared hundreds of thousands of times((Ruiz, Rebecca (2017): Don’t ban refugees. Ban garbage Facebook memes about refugees, in: Mashable, 03/02/2017, accessed on 07/03/2021.)), but the preparation of this discourse—loading its guns, as you will—had already been brought on by the NRA during the years preceding Trump’s candidacy. Before the NRA boldly endorsed Trump as “the choice for gun owners in this election”((Yablon, Alex; Freskos, Brian; Biette-Timmons, Nora (2016): How the NRA Stoked the Populist Rage That Gave America President Trump, in: The Trace, 11/11/2016, accessed on 05/03/2021.)), it had been “moonlighting as an anti-immigration group for years”((Weinstein, Adam; Spies, Mike (2017): The NRA Has Been Moonlighting as an Anti-Immigration Group for years, in: The Trace, 31/02/2017, accessed on 05/03/2021.)).

Conclusions

I started out covering arbitrary travel notebook designs about Iran, stumbled upon items about Afghanistan that are unsensitive, and ended up dealing with war-glorifying and outright xenophobic slogans on veteran notebooks that function as merchandize for a certain segment of Trump supporters, mainly to be found within the sphere of firearm apologists and alt-right proponents. Buying these items increases Amazon’s profit, as the company makes money from fees and sales, and fascilitates the sale itself by providing vendors with a content creation and sales platform, tools for advertisement and corporate brand trust.

I would like to stress that I distinguish between arbitrary items and items with deliberate political messages. As for the travel notebooks, one could argue that no general bad faith can be assumed, since the items are after all generated in bulk for many countries. Nevertheless, there seems to be a certain pre-selection of countries that can be considered for item generation according to certain design templates, because not all designs are offered for all countries. This pre-selection process therefore also includes, or rather does not actively exclude countries torn by war and terrorism. It is the prevailing conditions and the suffering of the populations of these countries that make happy travel journals and trendy Youtube travel vlogging about adventurous journeys to Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen so insensitive and uncomforting. I call these travel notebooks the epiphenomenon of the commodification of the ‘East’ because they set forth the assimilation of whole countries and show an insensitive handling and disregard of cultural and religious peculiarities, beliefs and cultural values.

The veteran notebooks are clearly the more problematic items, as they show a certain aestheticization of violence and are used as political statements. They might be niche products on Amazon, but they are more than mere byproducts or digital trash, for they are designed to respond to a certain need and help maintain a broader sentiment and can even support political movements. My conclusion is that Amazon enables and profits from them simply because it can. From a business point of view, revenue always trumps ethical standards, unless public pressure forces the company into one of its usual reactive phases of superficial damage control. Amazon treats its business opportunities the same as its employees: as long as it can profit from them without a truely hurting backlash from the public or authorities, ethical standards do not matter. It is unacceptable that Amazon makes money from xenophobic products and fascilitates their production and distribution.

Originally I had intended to publish this post in November last year while Trump was still in office. Now, after turbulent weeks that accompanied the transfer of power in the USA and with different narratives still competing to explain the nature of political crisis in the U.S., I finally found enough time to finish this piece. Although there is a new president residing in the oval office now, and the daily news cycle—at least for the U.S.—has returned to a more predictable pace and less alarmist tone, the living legacy of the Trump presidency and his countless associates is still looming in the background. In my opinion, Trump’s departure and the idealization of Biden as a democratic saviour should not obscure our view on the fatal, inhumane foreign policy of the U.S. in Afghanistan and the WANA region during the presidential terms that preceded Trump, a policy that still continues to this very day, and for which Biden was co-responsible as vice-president during the Obama years. How tempting all simplistic explanation attempts might be, the worldview of Trump and his supporters can neither be encapsulated in the four years of his presidency, nor can it be contained by labeling it a mere contemporary movement or aberration. It is not a passing postmodern phantom, it transcends the run-up to and aftermath of Trump’s term in office. It emerged on a solidified breeding ground having deep roots in nationalism, chauvinism, firearm fanaticism, military heroism, and racism, and as shown above branches out into unexpected niches. Moreover, this breeding ground has proven ideal for the institutionalization of conflicting interests, in which the Trump movement took on a catalytic role and was able to prevent necessary changes, also because it offered Trump opponents many opportunities to continue advocating a traditionally oppressive foreign policy. Therefore the need for deconstructing the complex as a whole continues to be acutely relevant.

Follow the blog

Subscribe to the Newsletter

Receive updates about the Toolbox and other fresh content, you may cancel anytime.